It's been too long since we took the time

No one's to blame

I know time flies so quickly

--John Lennon

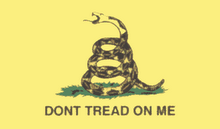

I view high profile court decisions as an opportunity for improving my understanding of the law, particularly as it relates to the Constitution and principles of liberty. These pages include reflections on several cases, including Obamacare, the Arizona immigration case, and the Zimmerman murder trial. The Ninth Circuit's recent decision to uphold a temporary restraining order on President Trump's travel ban provides another such opportunity.

The Trump's travel ban order is interesting to me because, at a high level, it pits freedom against security, a topic that has occupied this blog since its founding.

It also involves the Ninth Circuit. The Ninth Circuit is affectionately known to some as 'the Ninth Circus' because of its reputation to deliver some of the most unconstitutional rulings of any appellate court in the country (measured in part by the high percentage of its rulings that have subsequently been overturned by the Supreme Court). As such, its opinions often provide a useful contrast against which to evaluate legal correctness.

Much of the interest surrounding this case is Trump's campaign characterization of his executive order as a 'Muslim ban.' Trump's detractors, and the legal plaintiffs in the case, claim that this proves intent of discrimination on religious grounds. While this may of concern from a human standpoint, what matters from a legal standpoint is what is stated in the executive order. Plainly, there is no bias written into the order in this regard. Religious belief is not a basis for travel restriction; country of origin is. And although the Muslim faith pervades the several countries included in the ban, Muslims traveling from other countries are unaffected. Fortunately, although Ninth Circuit judges questioned federal lawyers about Trump's rhetoric and commented about it in their ruling, they did not base their opinion on this issue.

Did the plaintiffs, e.g., the state of Washington, even have standing in this case? The principle of standing holds that only persons legally injured by government conduct can sue to challenge legality. The Ninth Circuit ruling held that states can challenge federal immigration law on grounds that state institutions, such an universities, would be affected by the absence of students or faculty affected by the travel ban. This argument seems weak, and is analogous to Wal-Mart suing the government for taxes imposed on its customers because they would have less money to spend in the store. Moreover, state institutions are not the regulated party in this case. Instead, the plaintiffs are suing to block the enforcement of an executive order against other people, a situation for which there is little precedent.

A primary argument made by the plaintiffs is that the executive order violates due process rights of affected aliens. This is problematic for several reasons. One is that the president has been granted plenary authority by both the Constitution and by Congress under the Immigration and Naturalization Act (INA) to decide that aliens from particular nations present national security risks. Because they are unadmitted nonresidents, aliens have no constitutional right of entry into the United States.

The Ninth Circuit sidestepped this issue, arguing that aliens are being denied procedural due process in that they now have no 'notice or hearing' for making their case for entry. But aliens have no fewer procedural rights than they had under prior law. They can still apply for visas and protest cancellation of visas just as before. The executive order deals with substance, stating that aliens from several foreign countries will not be permitted to travel to the United States for a temporary period of time until security procedures are reviewed.

The Ninth Circuit spent several paragraphs explaining why the executive order might not be constitutional with respect to some groups, including green card holders, previously admitted aliens presently abroad, and even unlawful aliens now residing in the US. However, these groups represent a subset, perhaps even a small minority, of the scope of the executive order. Nonetheless, the law as written can be construed as incorrectly applying to some groups that are protected under the law.

The legal question is whether a law should be upheld when the scope, in terms of who is affected, has not been correctly specified. The court ruled, "Even though the TRO [the federal judge's block on the travel ban] may be overbroad in some respects, it is not our role to try, in effect, to rewrite the Executive Order."

I think the Ninth Circuit got this part right. Strike down a law (or uphold a restraining order) when it has been incorrectly specified. Don not try to recraft it from the bench. Parenthetically, recrafting it from the bench is precisely what the Roberts court did with Obamacare--not just once, but twice.

Since the appellate court decision, the Trump administration has signaled that they will not appeal the decision to the Supreme Court. This seems smart. Although it erred in much of its judgment, and it is questionable whether state plaintiffs in fact had legal standing to bring suit, the Ninth Circuit got its assessment of scope right.

In effect, the court has sent the executive order back to the president for a rewrite.

Saturday, February 11, 2017

Ninth Circuit Ruling

Labels:

education,

freedom,

immigration,

judicial,

liberty,

natural law,

security,

self defense,

Trump

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment