The highway's jammed with broken heroes on a last chance power drive

Everybody's out on the run tonight but there's no place left to hide

--Bruce Springsteen

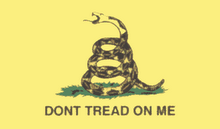

A popular view (and one promoted by many politicians) is that, in a free market system, power is held by the producers. Through this lens, capitalists are seen as antagonists and in need of government intervention and control.

Such perspective is misguided. In a truly free market, power is held by the buyers (Mises, 1949; Rothbard, 1962). Buyers decide what to purchase, and their purchasing decisions provide critical feedback to producers on what constitutes value. Through free exchange, customers steer economic activity towards innovation and efficiency (Schumpeter, 1942).

Bureaucratic intervention distorts this mechanism. Perversely, government regulation and control often hands more power to producers. For instance, regulation commonly erects entry barriers that discourage prospective entrepreneurs with potentially compelling value propositions from entering industries, thus protecting the franchises of incumbent firms (Porter, 1980).

Moreover, regulation atrophies the decision-making process of buyers. For example, bank accounts backed by federal government insurance (e.g., FDIC) has blunted the critical assessment process necessary for customers to determine the health of financial institutions they patronize.

Reduced due diligence by buyers increases the error in purchasing decisions. Inevitably, society's scarce resources will be mis-allocated as producers respond to distorted signals emanating from buyers.

Quite paradoxically, by seeking government-sponsored intervention and control over producers, buyers cede power that was originally theirs in a free market system.

no positions

References

Mises, L. (1949). Human action. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Porter, M.E. (1980). Competitive strategy. New York: Free Press.

Rothbard, M.N. (1962). Man, economy, and state. Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand Co.

Schumpeter, J.A. (1942). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. New York: Harper & Bros.

Saturday, June 28, 2008

Who's the Boss?

Labels:

bureaucracy,

capital,

competition,

democracy,

intervention,

markets,

moral hazard

Thursday, June 26, 2008

Gimme Shelter

Ooh, see the fire is sweepin'

Our very street today

Burns like a red coal carpet

Mad bull lost its way

--Rolling Stones

Common wisdom is that businesses dislike government regulation. A plausible rival hypothesis is that industry participants welcome regulation. Viewed through a strategic lens, regulation raises barriers to entry, thus protecting the franchises of incumbents.

Although popular history teaches that trustbusting activity of the late 1800s - early 1900s helped reign in rampant monopolies in oil, railroads, banking, and other sectors, Rothbard (2002) offers compelling evidence that incumbent firms proactively sought regulation as a means to preserve franchises that were under attack by slews of upstarts.

As such, regulation serves to reduce competition.

References

Rothbard, M.N. (2002). A history of money and banking in the United States. Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Our very street today

Burns like a red coal carpet

Mad bull lost its way

--Rolling Stones

Common wisdom is that businesses dislike government regulation. A plausible rival hypothesis is that industry participants welcome regulation. Viewed through a strategic lens, regulation raises barriers to entry, thus protecting the franchises of incumbents.

Although popular history teaches that trustbusting activity of the late 1800s - early 1900s helped reign in rampant monopolies in oil, railroads, banking, and other sectors, Rothbard (2002) offers compelling evidence that incumbent firms proactively sought regulation as a means to preserve franchises that were under attack by slews of upstarts.

As such, regulation serves to reduce competition.

References

Rothbard, M.N. (2002). A history of money and banking in the United States. Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

The Elephant Dance

Why don't you tell me what's going on?

Why don't you tell me who's on the phone?

--Fleetwood Mac

Sometimes you have to actually own a stock before you realize just how tenuous a situation is. Late last week I bought a couple of bank stocks thinking that the selling was overdone. Stalwart names like Wells Fargo (WFC) were yielding 5%+ and regionals like Sun Trust (STI) were yielding 9% or so.

As soon as I bought them, however, I knew I couldn't hold them. I felt the structural risk right away. Even if the fat dividends are safe (a big if), bank stock prices could easily melt below the margin of error afforded by the rich yields.

So, this nervous long 'fed the ducks' (read: sold) into the oversold bank stock rally over the last couple of days.

What did I learn? Now is not the time for me to initiate long term positions in the financial sector. And since I'm not a trader, my best course of action is to do nothing when I perceive risk this high.

no positions

Why don't you tell me who's on the phone?

--Fleetwood Mac

Sometimes you have to actually own a stock before you realize just how tenuous a situation is. Late last week I bought a couple of bank stocks thinking that the selling was overdone. Stalwart names like Wells Fargo (WFC) were yielding 5%+ and regionals like Sun Trust (STI) were yielding 9% or so.

As soon as I bought them, however, I knew I couldn't hold them. I felt the structural risk right away. Even if the fat dividends are safe (a big if), bank stock prices could easily melt below the margin of error afforded by the rich yields.

So, this nervous long 'fed the ducks' (read: sold) into the oversold bank stock rally over the last couple of days.

What did I learn? Now is not the time for me to initiate long term positions in the financial sector. And since I'm not a trader, my best course of action is to do nothing when I perceive risk this high.

no positions

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

Crude Awakenings

Out where the river broke

The bloodwood and the desert oak

Holden wrecks and boiling diesels

Steam in forty five degrees

--Midnight Oil

A few rules of thumb when trying to make sense of the current crude oil supply/demand landscape (in millions of barrels per day).

World supply = 85

World demand = 87 (world demand currently outstrips supply by 2 MBPD)

US supply = 7 (US produces about 1/3 of what it consumes)

US demand = 21 (US consumes roughly 25% of world production)

China demand = 7.5 (about 1/3 of US demand but growing @ 3x US rate)

OPEC supply = 30 (about 35% of world supply)

At current production levels, the world consumes about 31 billion barrels/yr.

no positions

The bloodwood and the desert oak

Holden wrecks and boiling diesels

Steam in forty five degrees

--Midnight Oil

A few rules of thumb when trying to make sense of the current crude oil supply/demand landscape (in millions of barrels per day).

World supply = 85

World demand = 87 (world demand currently outstrips supply by 2 MBPD)

US supply = 7 (US produces about 1/3 of what it consumes)

US demand = 21 (US consumes roughly 25% of world production)

China demand = 7.5 (about 1/3 of US demand but growing @ 3x US rate)

OPEC supply = 30 (about 35% of world supply)

At current production levels, the world consumes about 31 billion barrels/yr.

no positions

Saturday, June 14, 2008

In a Box

I've been looking so long at these pictures of you That I almost believe that they're real Been living so long with these pictures of you That I almost believe that the pictures are all that I feel

--The Cure

The technical concept that I like to call 'box theory' was made 'famous' by stock market speculator Nicolas Darvas (1960). It proposes that, in a bull market, prices advance in cells or boxes that can be readily tracked.

We can apply box theory to the bullish gold move over the past 3-4 years. Four boxes have defined gold's move off the long base in 2005. Each box has ranged about $150.

Moreover, it appears that there have been two different types of boxes. An advancement box has been characterized by a rapid price rise thru the entire price range up into the next box higher. That advancement continues into a consolidation box, where prices spike up to the top of the box range, pull back, and then endure a period of consolidation before heading higher into the next advancement box.

Currently, we're in a consolidation box ranging from about $850 to $1000. In the previous consolidation box, we spent more than a year, well, consolidating. Will we need to do the same thing this time before (if) gold moves higher?

Let's see what happens.

position in gold

References

Darvas, N. (1960). How I made $2,000,000 in the stock market. New York: Carol Publishing Group.

--The Cure

The technical concept that I like to call 'box theory' was made 'famous' by stock market speculator Nicolas Darvas (1960). It proposes that, in a bull market, prices advance in cells or boxes that can be readily tracked.

We can apply box theory to the bullish gold move over the past 3-4 years. Four boxes have defined gold's move off the long base in 2005. Each box has ranged about $150.

Moreover, it appears that there have been two different types of boxes. An advancement box has been characterized by a rapid price rise thru the entire price range up into the next box higher. That advancement continues into a consolidation box, where prices spike up to the top of the box range, pull back, and then endure a period of consolidation before heading higher into the next advancement box.

Currently, we're in a consolidation box ranging from about $850 to $1000. In the previous consolidation box, we spent more than a year, well, consolidating. Will we need to do the same thing this time before (if) gold moves higher?

Let's see what happens.

position in gold

References

Darvas, N. (1960). How I made $2,000,000 in the stock market. New York: Carol Publishing Group.

Sunday, June 8, 2008

Gushing Cash

With a little perseverance you can get things done

Without a blind adherence that has conquered some

--Corey Hart

In a previous missive we discussed the merits of free cash flow for valuing securities. To get a feel for this concept in motion, let's take a look at a company that has been generating mammoth free cash flow, Exxon Mobil (XOM). Recall that free cash flow (FCF) equals operating cash flow (OCF) minus capital expenditures (capex).

You can see that XOM's operating cash flow has increased by about 150% over the past few years. During this period, capital expenditures have increased less than 50%. As a result, free cash flow has increased nearly fourfold, reaching nearly $37 billion in 2007.

This is a remarkable level of FCF--even for enterprises in the 'sweet spot' energy space. Indeed, many favorite domestic 'go to' trading names in oil and gas production, such as Apache (APA), Devon Energy (DEV), and XTO Energy (XTO) have not been consistently FCF positive throughout this same period. While operating cash flows have increased significantly for these enterprises, capital expenditures have increased commensurately, leaving less FCF than one might expect given the favorable secular winds blowing at the backs of firms in this sector.

One of the first things that I do when examining an investment idea is to review historical FCF trends (similar to what we've done above). This exercise helps me get a toe hold on the economic value producing potential of an enterprise.

How can we use FCF info to estimate the 'fair value' of a stock? Stay tuned.

no positions

Without a blind adherence that has conquered some

--Corey Hart

In a previous missive we discussed the merits of free cash flow for valuing securities. To get a feel for this concept in motion, let's take a look at a company that has been generating mammoth free cash flow, Exxon Mobil (XOM). Recall that free cash flow (FCF) equals operating cash flow (OCF) minus capital expenditures (capex).

Annual XOM Free Cash Flow ($ Billions)

| Year | OCF | Capex | FCF |

| 2002 | 21.3 | 11.4 | 9.8 |

| 2003 | 28.5 | 12.9 | 15.6 |

| 2004 | 40.6 | 12.0 | 28.6 |

| 2005 | 48.1 | 13.8 | 34.3 |

| 2006 | 49.3 | 15.5 | 33.8 |

| 2007 | 52.0 | 15.4 | 36.6 |

You can see that XOM's operating cash flow has increased by about 150% over the past few years. During this period, capital expenditures have increased less than 50%. As a result, free cash flow has increased nearly fourfold, reaching nearly $37 billion in 2007.

This is a remarkable level of FCF--even for enterprises in the 'sweet spot' energy space. Indeed, many favorite domestic 'go to' trading names in oil and gas production, such as Apache (APA), Devon Energy (DEV), and XTO Energy (XTO) have not been consistently FCF positive throughout this same period. While operating cash flows have increased significantly for these enterprises, capital expenditures have increased commensurately, leaving less FCF than one might expect given the favorable secular winds blowing at the backs of firms in this sector.

One of the first things that I do when examining an investment idea is to review historical FCF trends (similar to what we've done above). This exercise helps me get a toe hold on the economic value producing potential of an enterprise.

How can we use FCF info to estimate the 'fair value' of a stock? Stay tuned.

no positions

Wednesday, June 4, 2008

Money Tree

We mention the time we were together

So long ago, well I don't remember

All I know is that it makes me feel good now

--The Motels

Per Mises (1934), there are three primary categories of money. Commodity money is employed as a medium for exchange (exchange is the primary function of money) due to its technological characteristics (scarcity, portability, etc.). Gold has commonly been employed as a commodity money.

Fiat money possesses a stamp from an authority that 'makes' it money, although this money possesses few of the technological characteristics that make it attractive for exchange. The US Dollar has been declared 'legal tender' by the US government. Our 'official' money.

Credit money is a claim falling due in the future that is used as a general medium of exchange. Loans of all sorts provide a means of exchange for the borrowers.

Which of these monies have been on the rise, and which on the decline, for the past century or so?

position in gold

References

Mises, L. (1934). The theory of money and credit. London: Jonathon Cape Ltd.

So long ago, well I don't remember

All I know is that it makes me feel good now

--The Motels

Per Mises (1934), there are three primary categories of money. Commodity money is employed as a medium for exchange (exchange is the primary function of money) due to its technological characteristics (scarcity, portability, etc.). Gold has commonly been employed as a commodity money.

Fiat money possesses a stamp from an authority that 'makes' it money, although this money possesses few of the technological characteristics that make it attractive for exchange. The US Dollar has been declared 'legal tender' by the US government. Our 'official' money.

Credit money is a claim falling due in the future that is used as a general medium of exchange. Loans of all sorts provide a means of exchange for the borrowers.

Which of these monies have been on the rise, and which on the decline, for the past century or so?

position in gold

References

Mises, L. (1934). The theory of money and credit. London: Jonathon Cape Ltd.

Monday, June 2, 2008

Rip Tide

Nothing is planned

By the sea and the sand

--The Who

Common wisdom is that higher commodity prices signal inflation. But what if higher crude et al prices are a late stage symptom of expanding credit? Stock, bond, real estate prices lead as financial institutions have first crack at institutionally (read: Fed) created credit. Only later does that leverage filter into commodity prices and finished goods prices.

Shouldn't higher goods prices slow demand down (ECON 101)? And, if economic activity slows down, what are the consequences in a highly leveraged system?

Given our leveraged situation, higher commodity prices seem more likely to sow seeds of a deflationary (not inflationary) bust.

no positions

By the sea and the sand

--The Who

Common wisdom is that higher commodity prices signal inflation. But what if higher crude et al prices are a late stage symptom of expanding credit? Stock, bond, real estate prices lead as financial institutions have first crack at institutionally (read: Fed) created credit. Only later does that leverage filter into commodity prices and finished goods prices.

Shouldn't higher goods prices slow demand down (ECON 101)? And, if economic activity slows down, what are the consequences in a highly leveraged system?

Given our leveraged situation, higher commodity prices seem more likely to sow seeds of a deflationary (not inflationary) bust.

no positions

Labels:

commodities,

deflation,

energy,

inflation,

leverage

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)