"Gentleman, whenever you have a group of individuals who are beyond any investigation, who can manipulate the press, judges, members of our Congress, you are always going to have in our government those who are above the law."

--Nico Toscani (Above the Law)

Columbia law professor Philip Hamburger discusses administrative law. Administrative law is binding edict that comes from administrative acts rather than legislative process. In the United States, the primary source of administrative law is the executive branch. The president, through executive orders or agencies, circumvents the two avenues of binding power established by the Constitution: acts of Congress and acts of the courts.

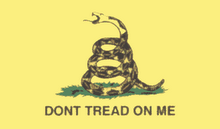

With the stench of despotic oppression still palpable, our founding ancestors steered away from empowering the executive branch with capacity for discretionary rule.

While conventionary history generally claims that administrative power was a product of post-constitutional US federal government development and is a modern necessity, Hamburger argues that administrative law as practiced today is merely the reemergence of absolute power practiced by pre-modern kings. Rather than a modern necessity, administrative law constitutes a threat inherent in human nature and the temptations of power.

The past one thousand years records ebb and flow between absolute power and legislative power. Time and again, kings were expected to govern through the acts of legislative and judicial bodies. Time and again, kings grew discontent with these legally binding constraints and began acting on their own. Hamburger calls their discretion "prerogative power."

Through prerogative power, kings had the authority to exercise force on legislative and judicial branches, enabling the enactment of personal decrees. Through their issuance of their discretionary proclamations, kings operated above the law.

Our founding ancestors were quite familiar with prerogative power and discretionary rule. They crafted the Constitution to bar capacity for administrative law.

At the same time, however, prerogative power was evolving. Particularly in Germany, what had once been the discretionary rule of kings was becoming the bureaucratic power of states. By the 19th century, Germany had become the mecca theories of administrative power, including those of the Marxian socialist variety. After thousands of intellectuals made pilgrimages to the Continent to study them, German theories of administration became standard fare in American universities.

By the early 20th century, the Progressive movement had embraced administrative law in America as a pragmatic and necessary instrument of modernity. A president unshackled by constitutional restraints was able to govern more effectively in changing and modern times, Progressive doctrine claimed. FDRs tenure became the ultimate expression of this doctrine in America, although it was well represented elsewhere through the likes of Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini, and others.

Today, it is often argued that Congress validly uses statutes to delegate lawmaking power to the executive branch. Hamburger observes that such a process is not new. Delegation of lawmaking has often been a feature of absolute power. Against this background, the Constitution expressly bars delegation of legislative power. The first words of Article 1 read:

All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States

"All" was not placed there by accident, as the framers understood the delegation problem in English constitutional history.

Rather than being a novel consequence of modern progression, today's administrative law reflects another round of pathological regression.

Friday, January 2, 2015

Administrative Law

Labels:

capacity,

Constitution,

Depression,

education,

EU,

founders,

natural law,

Obama,

socialism,

war

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment