I would do anything

To hold on to you

Just about anything

That you want me to

--Ric Ocasek

Emotions are part and parcel of the human condition. Through a philosophical lens, emotions are often viewed as contributing 'spice' to life.

From a cognitive standpoint, emotions constitute a mechanism for constraining and directing attention (Matthews & Wells 1994). Because they offer capacity for 'framing,' or for winnowing the number of possible considerations to a manageable number for deliberation, emotions can be a useful component of rational thought.

However, we also know that emotions can impair reasoned thought process. For example, emotions can influence interpretation of past events (Kahneman 2000), recognition of temporal cause and effect relationships (Thaler & Johnson 1990), and assessment of risk and reward (Kahneman & Tversky 1979).

Under conditions of threat, emotional framing mechanisms may 'overshoot,' leading to an excessive narrowing of information processing that inhibits generation of well reasoned solutions for coping with the threat (Staw, Sandelands, & Dutton 1981). Individuals are often unaware of the role of emotions in shaping their decisions (Fingarette 1969).

A common expression of emotional influence on decision-making is confirmation bias. Confirmation bias involves the tendency of individuals to seek and side with information that supports their beliefs, while avoiding or dismissing information that refutes their beliefs (Lord, Ross, & Lepper 1979). Confirmation bias can impair critical thinking because it demotivates search for informed alternatives.

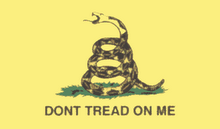

Confirmation bias is on my mind because of the current election context. And examples abound of confirmation bias among individuals engaged in political decision-making processes. Consider for example those folks who can readily recite a laundry list of defects regarding the opposition while staunchly dismissing all claims made against their preferred candidates. Processes and content of other political phenomena, such as rallies, satire, and political ads all seem consistent with exciting the reactive, emotional limbic system rather than other portions of the brain that support careful, reasoned thought.

In a democracy, one sided bias of political thought is sometimes viewed as acceptable because aggregating biased choices made during an election purportedly reflects a homogenously wise 'voice of the people' that magically corrects for individual bias (Surowiecki 2004).

Such a view seems misguided. Because individuals make choices, if voter thought processes are poorly reasoned, then election outcomes may not reflect collective wisdom. Instead, they seem more apt to reflect the aggregate ignorance of individuals.

References

Fingarette, H. 1969. Self-deception. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Kahneman, D. 2000. "Evaluation by moments: Past and future." In D. Kahneman & A. Tversky (eds.), Choices, values, and frames, pp. 693-708. New York: Cambridge University Press and the Russell Sage Foundation.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. 1979. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47: 263-291.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. 1979. Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37: 2098-2109.

Matthews, G. & Wells, A. 1994. Attention and emotion: A clinical perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Staw, B.M., Sandelands, L.E. & Dutton, J.E. 1981. Threat-rigidity effects in organizational behavior: A multi-level analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26: 501-524.

Surowiecki, J. 2004. The wisdom of crowds: Why the many are smarter than the few and how collective wisdom shapes business, economies, and nations. New York: Doubleday.

Thaler, R. H. & Johnson, E. 1990. "Gambling with the house's money and trying to break even: The effects of prior outcomes in risky choice." Management Science, 36: 643-660.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment