All for freedom and for pleasure

Nothing ever lasts forever

Everybody wants to rule the world

--Tears for Fears

Perhaps sensing what growing numbers are sensing after last week's oral arguments, President Obama stated that a Supreme Court ruling that strikes down Obamacare would amount to judicial activism. This is an ironic statement coming from a president with a hefty interventionist record himself. When measured in terms of spending, debt, regulations, bailouts, willingness to go 'over the heads' of Congress, etc, it can be construed that this president approaches FDR in activist tendency.

It is true that President Obama is not the first to toss claims of judicial activism toward the Supremes. Claims of activist judges have been around since the early days of the republic, although they have been escalating over the past 100 years.

However, it is unusual to hear activist claims muttered by a Democrat. More often than not, judicial activism is more likely an accusation of people who have opposed Supreme Court rulings that have favored liberal agendas.

What exactly is judicial activism? In simple terms, it is judges "taking the law into their own hands." The role of judges is to rule in accordance with the law. When judges rule in a manner that cannot be reasonably construed as lawful, then the ruling is activist in nature.

How one view 'law,' then, becomes central to evaluating the presence of judicial activism.

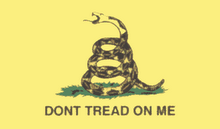

There are two primary views of what constitutes law. One view is that there is natural law that governs human action in the context of the functioning universe. This law gives rise to 'self-evident truths' as expressed by Jefferson, and certain axioms of nature and of human behavior that any social system must cope with. While not a perfect reflection, the Constitution is based upon a foundation of natural law.

A second view of law is the positivist view. Positivism proposes that there is no natural or moral basis to law. Instead, laws are 'posited' by human beings and are valid if they are enforceable. A popular expression of positivism is democracy. If a law can be enacted by majority vote, then it is legitimate.

The ink was barely dry on the ratified Constitution before interested parties sought to replace natural law with positivist law. The milestone case of Marbury v. Madison made it clear that the best path to implement positivist law was through the courts. Get a majority of Supremes to vote in favor of your proposal and, voila, your proposal becomes law--regardless of whether it aligns with natural law or not.

Thus, laws began to march to the Supreme Court for judicial review. Initially, and with a few notable exceptions, the Supreme Court defended the Constitution and natural law. Over time, however, presidential authority to appoint judges fostered the inevitability of a high court packed with interested positivists.

By the time of the New Deal, positivists were ruling in favor of laws, in cases such as Wickard v. Filburn, discarded by previous courts. The written opinions of assenting judges applied either a) tortured logic seeking constitutional justification for their verdicts, or b) arguments that this was a new era where the Constitution no longer applied.

This was judicial activism in its classic form. And cries of such could be heard from people who understood the consequences of moving away from natural law.

However, positivists literally ruled the day. From the early 1940s to the mid 1990s, not a single law passed by Congress was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

Now, much of what passes as law is grounded in precedents legitimized by activist judges. Proponents of those laws, such President Obama, defend them on grounds that legal precedents validate them.

This is positivism at its finest. Because a similar law was deemed legitimate by previous group of judges, then that precedent justifies a the new law. And if that precedent is not upheld, then it is 'judicial activism.'

It should be readily apparent to the reasoned mind that precedents grounded in positivism are not valid precedents at all. Rather, they are but steps in a random walk away from freedom toward tyranny.

Tuesday, April 3, 2012

Judicial Activism

Labels:

Constitution,

debt,

democracy,

Depression,

health care,

intervention,

judicial,

natural law,

Obama

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

1 comment:

Most high courts in other nations do not have discretion, such as we enjoy, in selecting the cases that the high court reviews. Our court is virtually alone in the amount of discretion it has.

~Sandra Day O'Connor

Post a Comment