All for freedom and of pleasure

Nothing ever lasts forever

Everybody wants to rule the world

--Tears for Fears

The presidential election of 1800 was a 'rematch' of the intense debates that took place during the constitutional ratification process a dozen years prior. In one corner were the Federalists with their incumbent candidate John Adams. The Federalists, politically close to modern Big Government Democrats and Republicans, favored a broad reading of the Constitution in which a strong central government prevailed over weaker states.

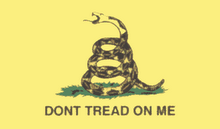

Many people were not pleased with the power that the federal government had been assimilating under the Federalist regimes of Washington and Adams. High profile dissenters included Jefferson and Madison, who saw the country veering away from the original intent of the Constitution. Thus, the Democratic-Republican Party was born, with a Jefferson presidential ticket in play for the 1800 election.

Parenthetically, the Democratic-Republicans were popularly referred to as the Anti-Federalists as people resurrected the familiar label from the old Constitutional debates.

A hard fought election found the Anti-Federalists winning the day--not only of the presidency but also of control of Congress.

Wishing to maintain power through the judicial system, the lame duck Federalist Congress passed a law that created 42 additional federal judges in February 1801. Two days before he left office, Adams appointed Federalist judges to assume these newly created benches to 'pack the court' in his party's favor. These appointees became known as the 'Midnight Judges.'

William Marbury was one of those appointees. He was nominated to be Justice of the Peace in Washington DC, which was the lowest rank of all Adams appointees.

To extend the Federalist judicial power grab, John Marshall, who was Adams' secretary of state, took over as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court on March 3, 1801. The next day Marshall swore in Jefferson as the 3rd president of the United States.

When Jefferson was sworn in, several Midnight Judges, including Marbury, had yet to receive their official commissions. Jefferson swiftly moved to declare these commissions null and void--basically because the official paperwork never came through under the Adams administration. Jefferson's newly appointed secretary of state Madison was instructed not to hand over any more commissions to the Midnight Judges.

Marbury sued, and took his lawsuit directly to the Supreme Court, pursuant to the Judiciary Act of 1789. Marbury sought a writ of mandumus--a court order requiring a government official to carry out a nondiscretionary appointment. Stated differently, Marbury wanted a court order that forced Madison to hand over his commission.

The Supreme Court headed by Marshall pondered the case for two years. While it appeared that Marbury had earned a valid commission, the High Court was distrubed by the Judical Act of 1789 itself. The Act, i.e., Congress, gave the Supreme Court original jurisdiction for cases like Marbury's.

However, the Constitution did not. Constitutionally, original jurisdiction for the Supreme court is limited to "all cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party. In all other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdication." (Article 3, Section 2)

The Court reasoned that, although the Judicial Act of 1789 gave the Supreme Court authority to afford a remedy to Marbury, the act of Congress authorizing the Court to hear the case was not grounded in the Constitution. The Court's authority was therefore null and void.

Coming from a unanimous opinion written by Chief Justice John Marshall, this was a remarkable ruling. Despite his Federalist urges to centralize power (and he would indeed satisfy those urges in later rulings), Marshall could not reasonably deny the limits to government power defined by the Constitution--at least in the case. As Marshall saw it, Congress is a creature created by the Constitution; Congress does not have the power to trump its creator.

Marbury v. Madison is the most important legal case in US history because it established the principle of judicial review. Judicial review is the power of the Supreme Court and all federal courts to examine statutes (and presidential behavior) and to declare them void if found to be inconsistent with the Constitution.

Marshall wrote: "it is the very essence of judicial duty to decide if two laws conflict, which shall supercede, and whether any laws conflict with the Constitution, which is superior and must prevail."

This is a position wholly consistent with Natural Law, upon which the Constitution is based.

It did, however, create a politically sticky issue. With Marbury, the High Court granted itself the authority to declare the will of the people (as represented by Congress) null and void if that will contradicts the Constitution. Positivists argue that the will of the people should prevail regardless of what the Constitution says. Moreover, they say, there is no such constitutionally enumerated power for the Court to rule on a statute's constitutionality.

As such, Marbury can be seen as a two edged sword. It permitted judges to invalidate laws that violated the natural rights of individuals. However, it also gave the Supreme Court incredible trumping power.

It wouldn't take power hungry politicians long to figure out how to employ that judicial trumping power in their favor.

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Marbury v. Madison

Labels:

antifederalists,

Constitution,

founders,

freedom,

Jefferson,

judicial,

liberty,

natural law

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

1 comment:

The rights of persons, and the rights of property, are the objects, for the protection of which Government was instituted.

~James Madison

Post a Comment