Let me tell you how it will be

That's one for your nineteen for me

--The Beatles

The federal government has two primary ways to obtain economic resources. It can print money, thereby obtaining instant claims to resources that it did not create. Or it can appropriate economic resources directly from the people in the form of taxes.

For the first century or so of the country's existence, the federal government's capacity to tax was Constitutionally limited. Article 1, Section 9 restricted the central government from levying taxes directly on the people except for a head tax. Through the 1800s government inflows were confined mostly to ad valorem taxes and asset sales.

That all changed with the 16th Amendment, which permitted the federal government to tax income at its discretion.

Once the feds knew what they had, spending and debt have never looked back. (Source for the following data is the OMB website.)

Receipts and outlays exploded almost overnight, and helped fund a world war:

Of course, those early increases don't even show up as blips on a graph of the past 100 yrs given the massive increases in receipts and outlays over the past few decades:

Observe the widening chasm between receipts and outlays (about $1.3 trillion in 2010). The difference must be funded by either debt or money printing. We've been doing both.

There are many who think that the difference should be closed by increasing the tax burden. In 2010, federal government receipts totaled about $2.1 trillion, about 15% of GDP. Inflows on both an absolute and relative level are down slightly over the past two years--presumably because of a slower economy and less income to tax.

Individual income taxes and social security taxes each constitute about 40% of total receipts with corporate taxes composing another 10%. The remaining 10% is a blend of excise taxes and other revenue sources.

Since 1944, total government receipts as a fraction of GDP have been relatively stable, varying between 14% and 21% of GDP. The average is during this period is 17.8%.

Individual income taxes have largely varied between 6% and 9% of GDP, averaging 8.0% for the period. Social security taxes have trended up during the period while corporate taxes have trended down.

It is also readily visible in the above graph that the variance in overall inflows mirrors changes in individual income taxes. This is because of the gradual and opposite trends in social security and corporate receipts, along with income tax's major 40% role in overall inflows.

One final note before doing some math. The data above reflect federal government inflows only. If we add state and local receipts, the tax burden almost doubles. In 2010, total government inflows at all levels amounted to about $4.2 trillion, or about 29% of GDP.

Sourced from this nice analysis, here is a graph of overall government receipts:

Once again, note the step up after ratification of the 16th Amendment in 1913. It's been an uphill trip since, with only the occaisional economic slowdown slowing the ascent.

OK. The thesis by some is to close the federal government deficit by increasing individual income taxes. The federal deficit in 2011 is projected to be about $1.6 trillion. In 2010, individual income tax receipts totaled just about $900 billion. Eliminating the estimated 2011 federal deficit soley thru higher income taxes would require collection of $2.5 trillion from the people--about a 180% increase.

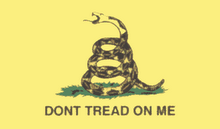

Tea stained Boston Harbor for lower tax hikes.

Which raises an interesting question. Just how much more could the federal government raise taxes if it wanted to? A theory often credited to economist Arthur Laffer posits that government tax rates pass through a maximum that is neither economically nor politically expedient to exceed.

Some believe that the federal government has already reached its taxation capacity. For example, Hauser's Law (named for some consultant in the 1990s who observed the phenomenon), says that the stable overall inflows as a % of GDP is empirical proof positive that that the federal government has reached the upper bound for taxation. This upper bound might reflect lower economic productivity as tax rates rise, tax payers exploiting loopholes in the tax code, and/or political fear of angering the taxpayers who are also voters.

Perhaps politicians are keenly aware that higher taxes and revolution are in this country's formative DNA.

Sunday, June 19, 2011

A Look at Federal Taxes

Labels:

Constitution,

debt,

government,

inflation,

liberty,

measurement,

socialism,

taxes,

Tea Party,

war

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment