Revvin' up your engine

Listen to her howlin' roar

Metal under tension

Beggin' you to touch and go

--Kenny Loggins

Astute investors such as John Hussman are offering cogent arguments as to why stocks offer long term value at these levels. My personal analysis also detects stock market value not seen in some time, although perhaps not as across-the-board as suggested by the work of others.

That said, a big risk to the 'stocks are good value at these levels' assessment is that investors (me included) may be overestimating future cash flows. As an example, consider a name that I'm involved with, Merck (MRK).

Currently, I'm estimating that MRK can generate $6 billion in annual free cash flow (FCF) over the long term (this is at the low end of MRK's annual FCF generation over the past few years). The value of that cash flow as a perpetuity discounted at 10% is $59.9 billion. A ratio of MRK's current market cap of $59.0 billion (stock price at Monday's close = $27.91) to this FCF perpetuity value = 59.0/59.9 or about .99. As such, MRK is selling for about a 1 percent discount using these assumptions and methodology. If we replace market value with enterprise value of about $52.9 billion, then this discount increases to about 12% (52.9/59.9 = .88).

The big 'if' here is our assumption of future free cash flow. What if MRK doesn't approach this FCF level? If, for instance, MRK's long term FCF generating power turns out to be only $3 billion annually, then MRK stock is currently overpriced, selling for about 2x fair value.

How might such a situation come about? Well, MRK could run into business or industry specific problems that drastically reduce the company's earning power. Depleted drug pipeline, increased bargaining power of buyers, legal actions, etc.

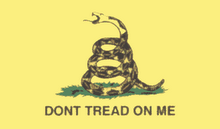

While such events are certainly within the spectrum of possibilities, I'm more concerned about changes to overall market structure that could permanently impair capital returns at firms across the board--not just at Merck. Specifically, I'm worried about the consequences of pervasive bureaucratic intervention in markets that we've experienced and may continue to experience moving forward. Persistent government meddling dramatically increases the probability of capital misallocation over time. Future returns on that capital and resulting free cash flows will almost certainly be reduced.

If returns on capital will indeed be chronically impaired, then those who are valuing stocks under the assumption that equities will ultimately revert towards historical cash generation patterns may produce over-optimistic forecasts.

The boilerplate warning that 'past performance may not be indicative of future returns' seems particularly appropriate when governments are assuming increased control over markets.

position in MRK

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment